Brad Fregger: Our next speaker is Max Hunter of Lockheed Missiles and Space Co. Max has been involved in the future most of his life. I said before, that none of us can live in the future, we live today. Max may be the exception; he may just be back here visiting us. Max is always out ahead a little, and if you were at our conference last year, you will remember he was the one that suggested there might be an inter-galactic community out there and we may well be a part of it someday. That’s thinking quite far into the future, and I’m sure today he will have more stimulating thoughts for us. Maxwell Hunter.

Mr. Maxwell Hunter, II

|

“THE RELATIVITY OF RELEVEANCE” |

One of the problems in thinking about the future, there are times when you know you are getting into a difficult situation and there isn’t anything you can do about it.

This morning while driving down, I negotiated a pact with my wife, we would be quiet so I could mull over once again what I was going to say this morning, it was quite a negotiation! What I didn’t tell her was going through my mind was that once again I was on the program following Bruce Coleman, and I recall, before, that was quite an act to follow. I can just see it happening again. It occurred to me that he gets to practice every Sunday morning and I don’t. There is nothing I can do now about this, except to try to recoup.

There was no way of defining an absolute … hence the name “Theory of Relativity.” Einstein stated that any really meaningful relationship between physical quantities had to take the same form when measured with respect to any frame of reference. This was a very startling presumption for his day, since it had been widely accepted that there were basic frames of reference which gave the true relationships without regard to the rest of the universe.

If one simply replaces “mathematical frame of reference” with “sociological frame of reference (sub-culture)” in the above statements, the reason for wondering if anything could be learned by analogy to Einstein’s work is immediately evident. Our view of life would certainly be drastically changed today if everyone were forced to consider only those things true which could be shown to be true in all social frames of reference. Make no mistake about this … the physicists were forced to accept Einstein’s theory by immutable experimental facts, not intellectual logic.

In order to understand the implications of his basic premise, Einstein found it necessary to examine in detail the mechanization of the transfer of information from one frame of reference to another. By doing this he was able to deduce the relationships which were identical for all frames of reference. In this process, the velocity of light emerged as a central feature of his theory. The reason is very straightforward. The velocity of light in a vacuum is the fastest and most constant thing that man has ever measured and, therefore, represents the fastest and most reliable means of transmitting information from one frame of reference to another. It is finite, however, and the Einstein relationships were derived by incorporating the effects of this finite information transmission velocity into the observed physical laws. He was able to find totally unexpected relationships which were true for any frame of reference and have since been proven to be valid.

The key to Einstein’s thought process was a painstaking detailed analysis of some fundamental issues, perhaps the most noteworthy of which was the notion of simultaneity. If two people in different frames of reference which are moving at some relative velocity decide to synchronize their clocks, the finite speed of their communication makes this impossible to do unless they use the relationships dictated by the theory of relativity. The basic notion and some simplified relations are easy to grasp, but the resulting generalized mathematics are fierce.

Since Einstein was dealing in physical quantities, he assumed that the speed of information transfer was constant at the speed of light. This required, of course, that the transmitters and receivers of information were perfectly truthful, i.e., the entities involved understood perfectly what each other meant to communicate and no transmitter or receiver was trying to mislead the other. Physicists must make such assumptions, and it is at once clear that they deal with much simpler relationships than “social scientists.” Yet they have learned much truth in their understandings. It would appear that to earn the term “social scientist,” one would have to be a greater master of mathematics than Einstein. What might one learn by thinking in those directions?

When we consider the effects of a finite transmission time of sociological interactions, we run into the hazard not faced by Einstein. His postulations were both on bodies of predictable velocity and accurate. The transmission medium between social groups is neither constant nor accurate. Before the invention of modern communications, of course, the transmission of activities of one group of people to another group was slow … it sometimes took weeks (or years if the other side of the earth were involved.) Now, of course, it is likely to take only minutes, and in the case of television, fractions of a second. It now approaches the speed of light. Thus, a great speed-up in the transmission of apparent group attitude has occurred recently; and according to some, this is supposed to unify the human race.

Just because the signal transmission speed has increased greatly, however, does not mean that the information content of the signal is accurate. If one transmits a signal to another entity, furthermore, he can in no way be certain of the effect of that signal until he receives a transmission back, and not very certain even then. The process of exchange between two physical quantities is relatively straightforward. Between two human beings or groups of human beings, any transmitter or receiver most probably has biased the information.

The first receiver may have biased circuits which will not really perceive what was intended to be transmitted. That person, in turn, may re-transmit a further biased manipulation of the information. When it comes back to the original receiver, it may well once again be filtered with all sorts of biases. It is well known to psychologists that these filtering processes in humans can be very extreme, including complete inversion of the intent of the data. A great deal of back and forth transmission can occur with no meaningful information content exchanged. This, in an Einsteinium universe, is equivalent to a velocity of light equal to zero … a dark world, indeed.

Since it is the velocity of exchange of meaningful information which is pertinent, the recent improvements in the velocity of signal transmission do not necessarily lead to a more rapid exchange of meaningful information. In fact, it is equally likely that the contrary may happen. If the image transmitted is overly vivid or unusually repulsive to the receiver, the nature of the receiver filter circuits (which tend to reject unwanted ideas) may be exercised to a much higher degree and the data may be more thoroughly rejected than if it had come in a more palatable form. Lags in this kind of situation have led to a great deal of unpleasantness in the past history of the human race.

Half of the people who were involved in starting wars throughout history have been wrong. Had they known they were going to lose, they wouldn’t have either started the war or let themselves be forced into it instead of submitting. The examples from history on this subject are legend. It is possible to send signals in one group’s direction which, because they are ignored or returned in ambiguous fashion, can lead the transmitter to believe that he is dealing with a group which can easily be pushed around. Some have made drastic mistakes in this direction and one need not go back too far in history to look for examples – World War II subsequent to Pearl Harbor will suffice nicely. One might, in fact, define a catastrophe as the abrupt establishment of non-ambiguous relevance.

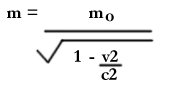

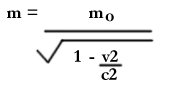

One of Einstein’s interesting results was that the mass of a body will increase as its velocity approaches the velocity of light, and it will become infinitely large at the velocity of light. It follows that nothing can go faster than the velocity of light. The actual relationship is:

Where:

mo = rest mass = mass at zero velocity

m = mass as measured by observer in different reference frame

v = relative velocity of reference frames

c = velocity of light |

In the social case, we can speculate that mass would be equivalent to social relevance, velocity equivalent to attempted rapidity of social change, and the velocity of light equivalent to the meaningful information transfer rate. Thus the rapidity of social change must be moderate with respect to meaningful information transfer rate, or it will appear to an observer in another reference frame that the social inertia is very high. Unfortunately, in the social case, the information transfer rate is highly variable, and can easily be zero. If we knew the true velocity of accurate information delivery back and forth between groups, we would likely discover some Einsteinian-like fundamental truths, not necessarily in the form of equation (1).

Separating the true signal from the noise is the essence of the problem. As an aid in this process, I suggest the use of another mathematical concept – this one due to Gauss. Gauss theorized that when dealing with populations of items or events, they tend to follow a law of probability which had a certain distribution which became known as the Gaussian distribution.

This distribution is a bell-shaped curve which, when applied to a group of people, can briefly be stated as … any group consists of a relatively small number of very good people, a relatively small number of very bad, and a great intermediate mass which are average.

If we postulate that all classes of people are made up of such a distribution (a relativity assumption with respect to the Gaussian distribution) then we have a mechanism for detecting false signals. This says that when dealing with college presidents, professors, high school students, football players, actresses, ditch diggers or policemen there are some good ones, some gad ones, but most fit some sort of an average picture. To describe any group as all good or all bad would obviously be a false statement. Thus, totally stereotyping one’s imagined enemies (or friends) and senselessly repeating the stereotype clearly shows up in this light as false data to be ignored.

The stereotype, of course, is useful. It is presumably defined by the mean of the Gaussian distribution of people of any group. In sports fields, stereotypes are frequently much more recognizable than in other groups. The group of professional football tackles, for instance, has certain mean characteristics of height, weight, and average velocity which are quite different from that of quarterbacks – and vastly different from the average male (or female) physique. But if one claims that all people of a given group have certain characteristics, he is then denying the existence of the Gaussian-type distribution and replacing it by a single characteristic at the mean.

There is, of course, fantastic evidence that this is wrong when dealing with human beings and this is a postulate which anyone can test with their own experience. It may be impractical to join other social groups and stay with them long enough to get to know the various people involved, to sort out their various characteristics, but it is clearly false to assume that they are all alike.

CONCLUSIONS:

Einstein’s theory of relativity, derived from the basis that no mathematical frame of reference is unique, could well have a social science analogy derived from the premise that no social frame of reference (subculture) is unique.

We should expect in such an analogy that the central position occupied by the velocity of light in Einstein’s relativity as the transmitter of information between reference frames would be occupied by the meaningful information transmission rate between the social groups.

In human information transmission, the fact that the transmitters and receivers may themselves, intentionally or unintentionally, distort the information must be considered, a point which did not need to be faced by Einstein.

The meaningful information transmission rate in humans can easily be zero, even when the signal transmission velocity is at the velocity of light as in the case of television.

If the actual social relationships had the same mathematical form as Einstein’s physical relationships, we would expect large distortions in the form of vastly increased apparent inertia if the social rate of change were to become large with respect to the meaningful information transfer rate.

The assumption that all the members of each non-unique group of people form a Gaussian distribution, the mean of which clearly approximates the popular stereotype of the group, should yield a helpful tool for separating the meaningful information transmission rate from the signal transmission rate, an obviously important problem.

We have a right to expect great things from such a theory of the relativity of relevance, but its derivation would require social scientists of mathematical expertise superior to Einstein’s, a not very likely combination.

Reference:

Hunter, Maxwell W. II, “Are Technological Upheavals Necessary?”, Harvard Business Review, September-October, 1969.